It’s well known that cows produce a lot of manure – so much so that our language contains more than a few cow-waste-related phrases for use among informal company.

What’s less obvious than the manure itself is the large quantity of methane that comes along with it. Methane is a highly potent contributor to the greenhouse effect and is released every time a cow poops, passes gas, or burps.

Cows don’t actually generate methane of their own accord. They break down tough grasses with the help of microbes that reside in their stomachs. It’s these microbes that produce methane as a waste product, and they do it both while they’re inside the cow and when they get expelled as part of the manure (National Geographic). There are a whopping 1.4 billion cattle in the world that, along with other grazers, produce 40% of the world’s methane totals. Manure in and of itself is also an environmental threat since it contains phosphorus and nitrogen. These are useful elements in fertilizer, but can get washed away as runoff to contaminate nearby bodies of water and generate more toxic substances (North Dakota State University).

On some modern dairy farms, cow manure is now being used to generate electricity. This is just one of the ways farms can prevent harmful methane gas from being released into the atmosphere. But how can cow dung be turned into energy?

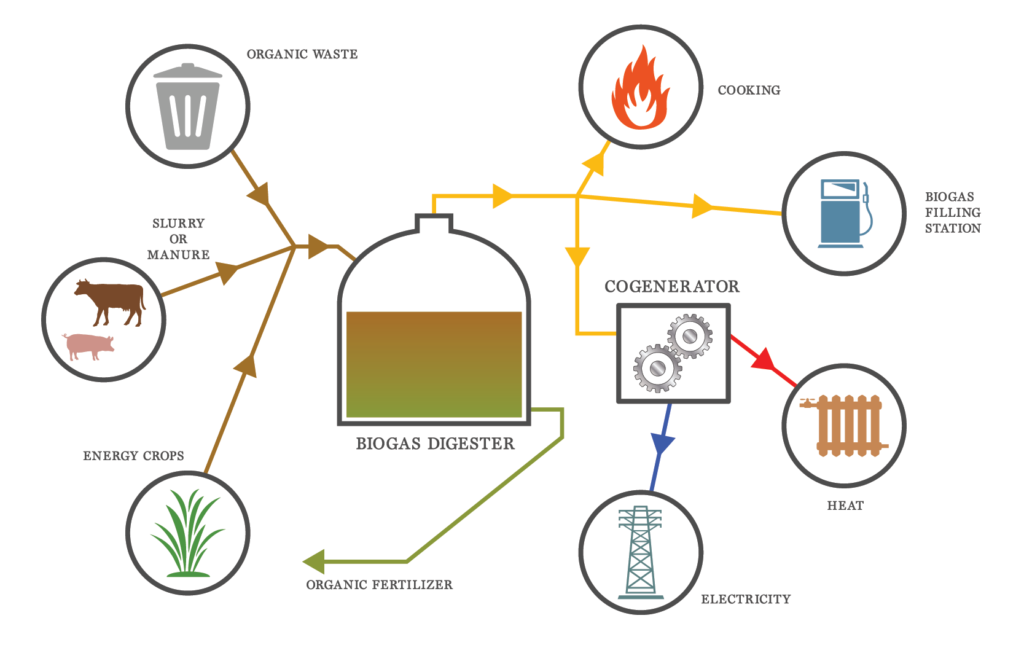

First, the cow manure and other waste liquids are dumped into a digester. The digester is an artificial container that functions much like a supersized cow stomach. This one, however, does not let waste gasses escape. Instead, it captures the gasses for later use.

The shapes and sizes of digesters vary from location to location. In California, they typically span the size of a football field and are covered in a sheet of plastic. In New York on the other hand, the digesters are more often built tall on a smaller footprint.

The facilities are kept at temperatures ranging between 100°F and 104°F, optimal conditions for the microbes. Inside of the digesters, bacteria break manure and other organic material down into smaller components. Among the products are the gases, CO2 (carbon dioxide), H2S (hydrogen sulfide), and CH4 (methane). The digesters then capture these gasses (sometimes referred to as biogas) for use in a power generator.

Most of us are familiar with the term, “natural gas.” The natural gas that gets pumped from underground wells is primarily composed of methane (plus a few other trace gasses) that was generated by decomposing plant matter and which has been trapped underground for millions of years. The bacteria that created that ancient gas performed much the same job as the modern bugs found in cow guts. It is not such a surprise, then, that the methane produced from manure digesters is so similar to natural gas, and either type can be used in the same burners and power generators.

There is a hitch to burning the resultant biogas, though, especially when it’s done in bulk. The dangerous and foul-smelling hydrogen sulfide first needs to be removed or at least brought down to safe levels. When combusted, H2S is converted into sulfur dioxide, or SO2. Sulfur dioxide pollution in the air is the primary cause of acid rain.

There are several methods to remove H2S, but arguably the most effective is iron hydroxide. The raw gas can be passed through a bed of FerroSorp or other such filter pellets. Sulfuric compounds will adhere to the filter medium and gradually be reduced into powdery elemental sulfur, which is much easier to dispose of. Some media expand markedly during this process, making them harder to manage, but FerroSorp iron hydroxide pellets are formulated to maintain their original volume while they work.

With the more dangerous constituents removed, the methane biogas is ready for use.

With some exceptions, the methane from a digester is converted into electricity on site; the output is typically not enough to make transportation of the gas itself very economical. Instead, it is burned to boil the water in an onsite generator, and the steam turns turbines to produce electricity. The overall size and output of the generator, of course, depends on the output of the digester. Larger generators are more efficient, but some farmers don’t capture enough gas to justify investing in a large machine. Farms can use the power on site or sell it to the power company as an additional source of revenue.

It’s worth noting also that once a digester is done creating methane, a number of products still remain. The leftover manure solids can still be used as fertilizer. They’re typically drier than they were at the beginning, making them much easier to transport.

It should be clear by now that the process of turning cow manure into electricity is not only good for the environment, but can be an economic boon as well. A committed farmer or businessperson can make the whole process, from digester to FerroSorp to generator, work to everyone’s advantage.